row2k Features

Peter Mallory's 'The Sport of Rowing'

Joe Burk, Sculler

"I happened to read about how well California had done in crew. I had never been to Poughkeepsie, scarcely knew where it was, but I found that I could take the train to New York and get on the New York Central to Poughkeepsie.

"I arrived there and didn't have any place to stay because every good place was already filled up, so I asked some bum on the street, and he told me of an old, brokendown hotel where I could eat and sleep.

"It was 1929, and California was the big-shot crew then. I wanted to see the time trials they were having, so I took the ferry boat across the river and went to the California boathouse.

"There was nobody around except the manager, and he showed me the shells and so forth. I found it all very interesting, and when the race came off, he and I dragged a railroad tie up against the side of the building, climbed up and watched the race from the roof.

"Unfortunately, California didn't win that year.

"Late in the day I went back to New York on the train. I stayed up the whole night and got home the next morning tired but knowing that I wanted to go out for rowing."856

Joe had exactly two cents left in his pocket.857

When Joe got to the University of Pennsylvania that fall, he almost missed his rowing destiny.

"I had been captain of my high school football team, and football was the big thing. I hadn't given any thought to the fact that they rowed in the fall in those days, and when I got to Penn, I found out that rowing started the same time that football practice did, so I thought that was the end of rowing for me.

"Then, after football I found out that crew started in on the machines in the winter, and so I met Rusty Callow and gave it a try."858

"He didn't make the first boat that year, but in the words of Callow, 'he combined those qualities of size, strength, skill and spirit' and made the varsity boat his sophomore year."859

According to Allen Rosenberg, "Joe was the epitome of a sportsman at Penn. He won two letters in football and crew, two blankets with a P on them. To have excelled in both in the same year is extraordinary."860 Joe tells me he actually won three letters in crew by the time he graduated in 1934, and Joe's son, Roger, tells me that Rusty actually had George Pocock make an oar with an extra-large blade for him to row with.

Joe: "At the time that I graduated in 1934, Penn planned to enter the Olympic Trials of 1936. To keep in shape in the meantime, I joined the Penn A.C., who had won the European Championship eights in 1930.

"They were coached by Frank Muller, Jack Kelly's sculling coach at the Olympics in the '20s, and he required all of his crew to have had sculling experience, so I was teamed with a young fellow, Tony Gallagher. He was a strong, young kid with no previous rowing experience. We made a good combination in the double and were undefeated.

"It was a good summer, and it prompted me to get a single built by George Pocock. "Gallagher hoped that we might compete together in the double in the Olympic Trials two years hence, but I had other plans, and that was to row in the University of Pennsylvania graduate eight, which was a strong crew."861

So, as Joe trained more and more in his single, he had as a foundation the fundamentals he had learned from Rusty Callow, and he also had as a sculling coach the man who had guided John B. Kelly to three Olympic Gold Medals. In addition, he began a regular correspondence with George Pocock that would last forty years.

But Joe Burk was also a free thinker. He approached his sculling with an open mind. He ended up developing a technique that built on but diverged completely from the 1st Generation Conibear Stroke he had rowed at Penn under Coach Rusty Callow.

Mendenhall: "He proceeded through trial and error rather than any prescribed lesson plan or time-tested technique. The experiment was rooted in Joe's growing conviction that the traditional, orthodox sculling stroke was inefficient and tiring.

"Though it was always seen as a continuous, unbroken cycle, the traditional stroke, even when racing flat out at a rating in the low to middle 30s, experienced some considerable alternation in speed.

"The shell always achieved its maximum speed at the finish of the stroke, and the recovery part of the cycle represented almost twice as much time as the drive through the water. Thus the sculler was traditionally obliged to pick up the boat up again every stroke at the catch.

"By contrast, Joe's eventual goal became clear: to keep the run on the shell virtually constant, with no variation in speed at either end of the stroke and most especially with no check or dousing at either the catch or the finish.

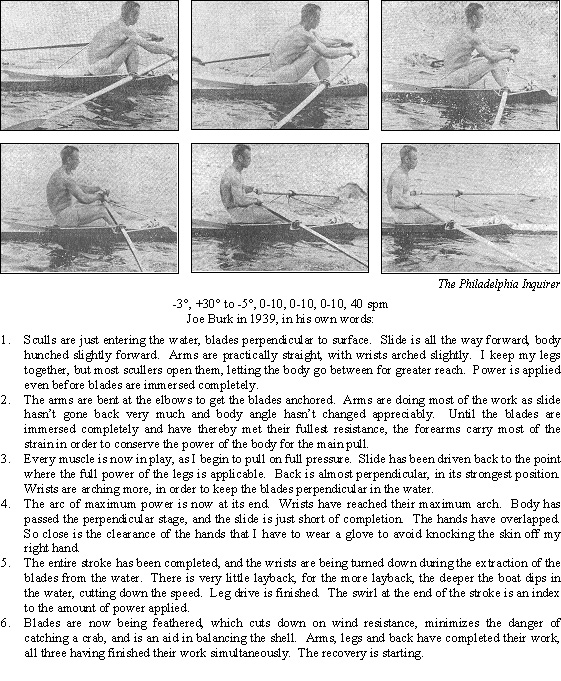

"Burk: 'The slide work is always the same, attempting to keep the slide moving continuously - no stopping, just a change in direction at either end. The arms, legs and back all started together and all finished together.'

"He reasoned that eventually the boat should move faster with less effort once he had shortened the stroke at both ends and conditioned himself to row comfortably at a much higher rating. The faster pull-through was helped by the knees remaining closed at the catch (to produce a quicker, straight-line drive) and the arms starting to break from the very beginning of the stroke."862

His contemporaries termed his technique "unique" and "innovative." In other words, they didn't know what to make of it. Nothing like it had been seen on Boathouse Row for half a century.

But it had been seen before.

Professional oarsman Barney Biglin, commenting around 1920 on a winning high-stroking Belgian crew at Henley, said, "I can't understand why there should be so much surprise in England because the Belgian crew manages to get great speed out of its so-called short, jerky stroke. What else could they get out of it? "863

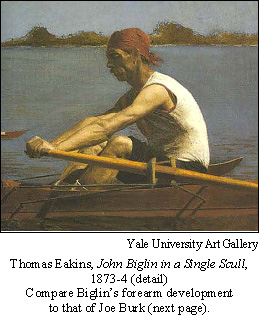

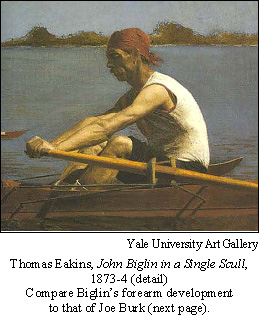

Barney and his brother, John, were painted by Thomas Eakins rowing their "short, jerky" stroke on the Schuylkill River in the early 1870s. Their forearm development foreshadowed that of Joe Burk.

For years after Joe bought his first Pocock single, he and George exchanged letters regularly, discussing equipment, training and technique.

For years after Joe bought his first Pocock single, he and George exchanged letters regularly, discussing equipment, training and technique.

"G.C. Bourne's A Textbook of Oarsmanship (1925), already the most thorough, scientific analysis of the conventional wisdom, insisted on at least a 1:3 ratio of pullthrough to recovery as fundamental to all good rowing!

"George Pocock came to recognize the possibility of the short stroke and high rating combined with Joe's training methods.

"'It's a wide opportunity,' he wrote, 'to anyone willing to pay the price.'

"[Joe's reply:] 'It was worth every tortured moment when the shell would feel silky smooth and go like a breeze.'"864

Upon his retirement, Joe wrote: "George Pocock of Seattle not only fashioned and constructed those sleek, slithering sticks of gold that were such a joy to scull, but also helped me no end in the art of sculling them.

"At times I am afraid George must have felt that he was running a correspondence course in the art of sculling, so many questions did I shoot at him by mail. It was he who convinced me that a short stroke would fulfill my requirements. His fame as a builder of racing shells has spread worldwide, but like Paul Revere's prowess as a silversmith, his ability as a sculling coach has been outshone by his other brilliance.

"To me it was a glowing beacon in the darkness of ignorance."865

Recently I asked Joe how he developed his approach to sculling:

Joe: "I tried many versions and came up with a technique that seemed to enable me to go sufficiently fast with a minimum of effort. It was very simple - arms, legs and back all started together and all finished together."866

"Most scullers' rate was about 28 strokes per minute, while mine was 40-42.

"Everyone else allowed one hand to precede the other, so they didn't overlap. I wanted to have them coming into my body at the same time. It required one rigger to be 3 1/2 inches higher than the other! Very unusual! However, it was very comfortable.

"Since I sculled with my hands moving at the same speed and crossing as they approached my knees, if my fingernails were the least bit long, they scraped the knuckles of my lower hand, so I wore a canvas glove from which I had cut off the thumb and fingers."867

"I added some padding made of the fingers that I had cut off, sewing with some heavy, black thread which my brother and I used for repairing baseballs as a kid. "We had a neighbor who pitched for a semi-pro team, and he gave us all the damaged baseballs in payment for being his catcher as he kept his arm 'loose' during the week."868

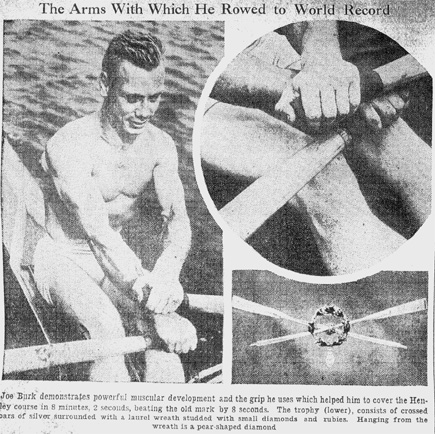

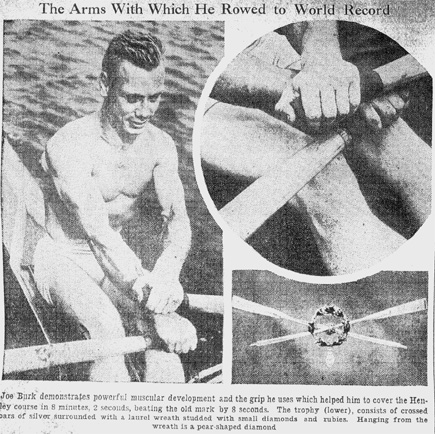

The Evening Bulletin, Philadelphia, July 2, 1938

Forearms to rival those of the Biglin Brothers

"The slide work [on the pullthrough and the recovery] was always the same, attempting to keep the slide moving continuously - no stopping, just a change in direction at either end."869

"[The technique] was not very fast, but sufficiently fast to win any race that was longer than a quarter-mile or half-mile."870 Sufficiently fast to win any race? Joe Burk is a very modest man.

At the 1936 Olympic Trials, his Penn graduate eight placed second to the University of Washington, and in his single, he placed second to U.S Champion Dan Barrow, who had rowed 7-seat in the Penn A.C. 1930 European Champion "Big Eight."871 That was the last race Joe lost for four years.

Joe won the 1937 U.S. and Canadian Championships, and then won them again every year through 1940.

He won the Diamond Sculls at Henley in 1938 and 1939. He amassed 37 consecutive victories in all, and won the Sullivan Award as the nation's top amateur athlete during 1939.

He won the 1940 Olympic Trials and would have been the overwhelming favorite at the 1940 Olympics in Helsinki, had they not been cancelled because of the outbreak of World War II.

How did Time Magazine describe his 1938 Diamond Sculls victory? "Britons who thronged the banks of the Thames last week for England's No. 1 rowing carnival, the annual Henley Regatta, saw an amazing performance.

"For four days they gaped at a redhaired American sculler, Joseph William Burk, who decisively outrowed his opponents over the mile and 5/16 course, day after day in the elimination heats of the Diamond Sculls, the most famed race in the world for individual scullers.

"'He does everything wrong,' muttered experts and dubs alike. Rowing an extremely high stroke (36 to 45 a minute, compared to an average sculler's 28 to 32), Joe Burk, who weighs 195 lb. and has arms like piano legs, propels his shell with an unorthodox short jerk of his arms and a quick kick of his legs, sits up almost straight at the end of each stroke.

"This freak style he developed two years ago on New Jersey's Rancocas Creek, hard by his father's fruit farm, after rowing in orthodox fashion on the University of Pennsylvania crew.

"He can row for miles at 40, and can maintain a speed of 12 miles an hour over a mile and a quarter course. Last year, after running away with the U.S. and Canadian sculling championships with machine-like ease, oarsmen dubbed him the "rowing robot," and marveled at the power of his arms. "But his brawny arms are nothing compared to his perseverance. In preparing for the Henley Regatta, throughout last winter and summer, the Jersey farm boy rowed 3,000 miles on the narrow, winding Rancocas, with a stopwatch strapped between his toes.

"Last week, 23-year-old Joe Burk was well rewarded. In the final of the Diamond Sculls, dipping his oars 45 times a minute, he streaked through the water as if he had an outboard motor attached to his 26-lb. shell, not only winning the coveted race but doing it in 8 min. 2 sec. - eight seconds faster than the Henley record set in 1905.

"'They'll have to burn all the books on rowing,' sighed onlookers."872

To put Joe's time into perspective, he broke a 33-year-old course record, and it only took another 27 years for it to be eclipsed.873 Diamond Sculls winners didn't begin to consistently row under Joe's time until the late 1980s, half a century after Joe.

How does Joe describe his achievement?

"I must admit that it was done under 'ideal' racing conditions."874

There have been a number of dominating scullers in rowing history, but the only man before or since who approached Joe Burk's innovative brilliance and athletic dominance was Ned Hanlan himself!

Fred Plaisted, the professional sculler who toured Europe with Jim Ten Eyck and actually rowed against Ned Hanlan in 1876, lived long enough to befriend Joe Burk.

He colorfully wrote about his fellow Boathouse Row sculler:

Fred Plaisted was 90 years old when Joe Burk won the Diamond Sculls in 1939, and I imagine that the wood-chopping president to which he was referring was Abraham Lincoln, whom he would have remembered well!

American Olympic coach Allen Rosenberg recalls, "Joe did the same thing as Ratzeburg [the innovative crew from West Germany] twenty years later. The rate of striking was so high that he had to cut both ends of the pullthrough."876

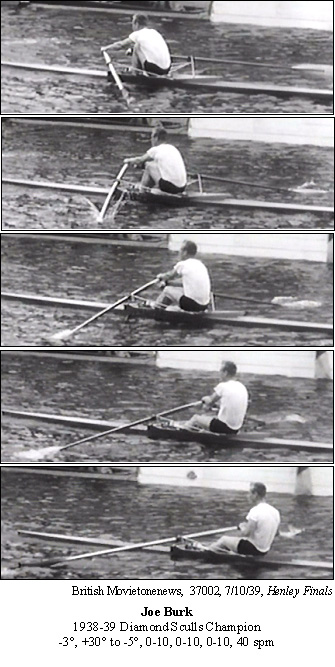

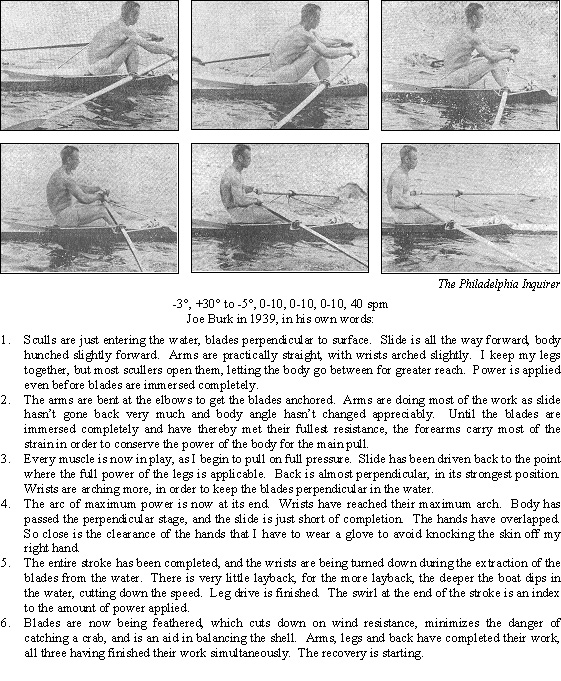

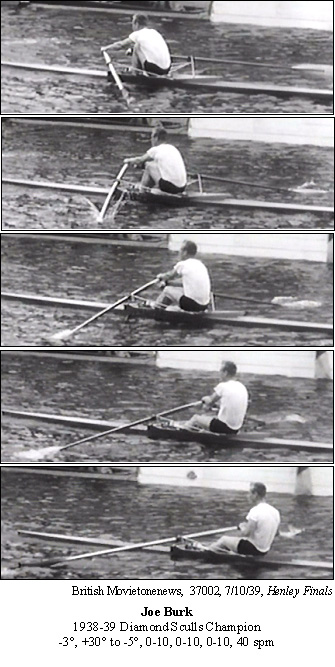

In fact, newsreel footage 877 reveals that Burk did not cut the front end of the pullthrough at all.

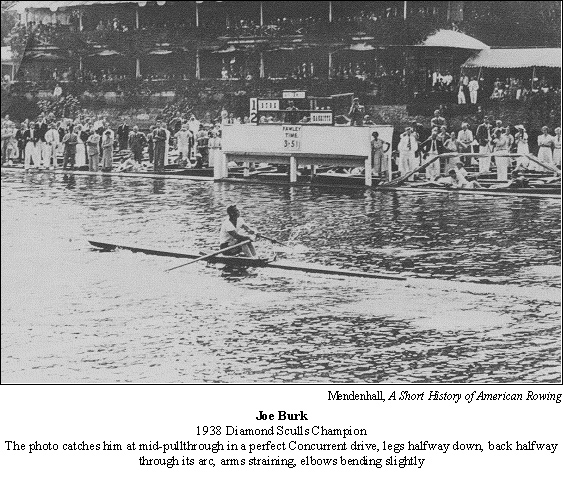

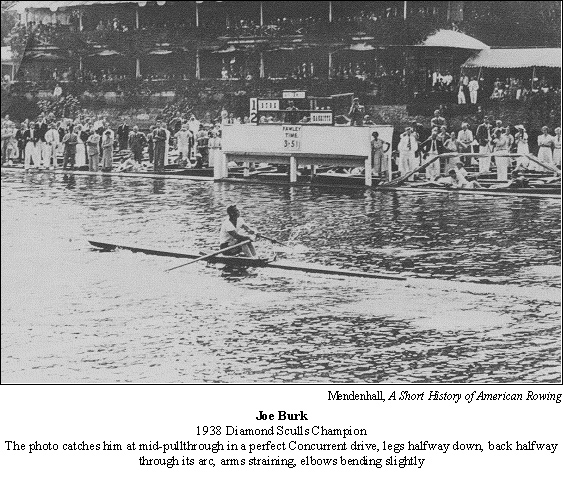

Joe Burk rowed that 1938 Henley final with a generous +30 degree body angle forward. His position at the catch was reminiscent of Ellis Ward's 1901 Penn Henley crew and Richard Glendon's 1920 Annapolis crew.

Much of his height was in his trunk, and he compressed his upper body tightly enough onto his thighs that his shins tilted past vertical.

His head followed an elegant arc up and away from the catch, and his shoulder lift and body swing were smooth and pleasing to the eye.

Burk's layback was limited to only -5 degrees, despite the fact that Callow had coached him at Penn to lay back -40 degrees or more, but his body swing as a whole was by no means radical. As we shall soon see, his concurrent usage of the legs, back and arms to a relatively upright finish mirrored the evolutionary direction of the 2nd Generation Conibear technique of Al Ulbrickson and Tom Bolles beginning in the early 1930s and reaching its height after World War II.

The Washington crew that beat Joe's Penn eight in the 1936 Olympic Trials had body swing from +25 to -25 degrees, considerably less than the norm of the time.

No. Limiting body swing was not Joe Burk's greatest innovation.

What seemed to set Burk apart was his rhythm, ratio and pacing, his ability to row an entire race evenly at a 1-to-1 ratio and not slow down.

He rowed the entire 1938 Henley final at close to 40 strokes per minute, certainly unique for a single sculler, but there truly is nothing new under the sun, and there had been precedents for Joe's high ratings.

Three years after high schooler Joe Burk had taken a train to watch them in Poughkeepsie, the California crew had won the 1932 Olympic eights by rowing the last 1,800 meters of the 2,000 meter course at 40 or above. They had to do so to match the Italians.

The New York Times: "At no time over the 2,000 meters were the blue-shirted men lower than 39 or 40 strokes to the minute, and toward the end their minimum was 42.

"Italy maintained an extremely high stroke throughout the race, which is characteristic of its style of rowing, featured like the American, by its short back swing, choppy stroke and short slide [my emphasis]."878

The margin of victory over Italy in 1932 was perhaps three feet. And 19th Century professional Barney Biglin used to brag, "Why, man alive, when we were winning championship races so fast that we could not count them, we used to hit it at 50 or even higher during spurts. The 50-to-a-minute stroke consisted chiefly of arm work, and forearm work at that, but it enabled us to get so far ahead that we could take a rest, so to speak."879

Interestingly, the last time Joe Burk ever raced in an eight was at the 1936 Trials, and his Penn graduate boat rowed the entire 2,000 meters at 40. They led for 1,600 meters before being rowed down. Perhaps it was here that Joe got the idea that he could make it those last 400 meters with just a bit more training.

No, Joe Burk's true innovation was imagination!

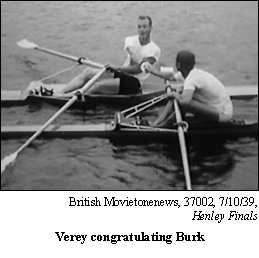

At the 1939 Henley Regatta, Joe deviated from his race plan, and he nearly regretted it.

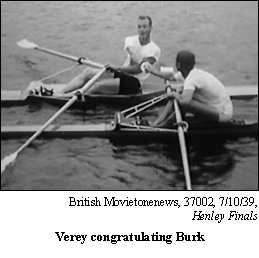

"A funny thing happened my second year in the Diamond Sculls during the final against Roger Verey from Poland. He had twice won the European Championships and was really quite a good sculler.

"With the way I rowed, I just learned from long experience never to worry about what happened at the beginning of a race because I knew that I could keep just about the same speed all the way through.

"So in my race with Verey, he went out and took a lead, and I caught up, oh, about halfway down the course.

"There was a strong cross-wind that day, especially there at the halfway point. I knew that my stern post was pointed right at the start float, but I hadn't thought about the fact that the wind was blowing me over.

"All of a sudden, Bang! I hit against an upright on the log boom.

"Luckily, I didn't capsize. My oar was turned up square at the time, and it was knocked out of my hands. I grabbed ahold of it, but by that time, Verey was back ahead of me.

"I thought, 'Boy! I'm really going to have to work now!' and I forgot all about pacing and just rowed as hard as I could.

"I finally caught up to him, maybe a quarter-mile from the finish. I started to go by him, but it was just about all I could do to keep moving.

"I knew he would look over at me, so as I began to go by, I turned my head and smiled at him as though there was nothing to it.

"Immediately, he dropped back, and that's the way I was lucky to win that second Henley victory."880

Just as with the West German Ratzeburg Technique twenty years later, the body mechanics of Burk's rowing technique was mainstream Schubschlag concurrent, but, as Adam would do again in the 1950s, Joe took the rating up, maintaining his smooth power application at a 1-to-1 ratio between pullthrough and recovery.

Just as with the West German Ratzeburg Technique twenty years later, the body mechanics of Burk's rowing technique was mainstream Schubschlag concurrent, but, as Adam would do again in the 1950s, Joe took the rating up, maintaining his smooth power application at a 1-to-1 ratio between pullthrough and recovery.

Interestingly, at Henley in 1938, British journalists saw a similarity between Burk and Steve Fairbairn: "He has invented a sort of Jesus Style of sculling [i.e. body swing insufficient to qualify as Orthodox]. He limits his swing strictly backwards and forwards, and within the narrow and highly efficient arc, he sculls with superb precision at 40 all over the course.

"His boat runs well with scarcely any hesitation or bounce . . . apart from the general crispness of his blade work, the strength of his wrist work at the finish is worth watching. . . .

"If he wins, he will have many imitators.

"It has been said that there never has been a man capable of sculling in Burk's style, but then no sculler of pretensions has ever been allowed by his advisers to try.

"Though it must need good wrists and a sound mind, there is some reason to suppose that this, in fact, is the least exhausting and most efficient way of propelling a sculling boat. No energy is wasted on pinching a boat, and the body is never in an exhausting position which hampers breathing . . . He is, in fact, the best balanced sculler ever seen.

"His short stroke, aided by unremitting practice, have made him so, and though his form may not be elegant [i.e. insufficient body swing] and he buries his oars a little too deep when tired, it seems as if from his time he would have relentlessly rowed down all the giants of the past . . . with his unemotional 40 strokes a minute."881

There was good reason that British journalists and Time Magazine were impressed with Burk's wrists. As Burk protege Harry Parker recalls, "He had massive forearms. When I was sculling with him, I remember that was the first feature that you would notice.

"One of the hallmarks of Joe's sculling was breaking the arms early and bending them continuously through the stroke, which, as he admits, put a tremendous strain on him, and it took quite a while for him to develop that strength.

"I talked to a guy at Penn who was in the gym with Joe and used to describe some of the workouts he did with these ball weights, you know pulling them, and he did phenomenal workouts strengthening up his arms, his forearms in particular."882

Of course, gym workouts were not Joe's only land training. At his farm, "climbing up and down the ladders with thousands of 50-pound baskets of apples provided him with plenty of weightlifting."883

I asked Joe what it was like to row the Burk Technique.

Joe: "When I first attempted it, I could go only a short distance before fatigue set in. So, I decided to scull every stroke in this manner.

"I used to practice day after day on the Rancocas Creek, where we had a farm. I even had to dodge the floating ice during the winter. I would be all alone - miles away from my little dock at home. If I had struck an ice-flow, it would have been curtains. I was just plain lucky."884

According to historian Mendenhall, "The outings began with short stretches to warm up with and then longer pieces at racing stroke, 36 the first year, then up to 38.

Eventually he was sculling for 20 minutes at 40-42. Everything was directed to eliminate all wasted motions, anything that might reduce the rate of striking with the slide continuously moving. The speed on the recovery was the same as on the pullthrough."885

In Burk's words, "I gradually adjusted to it. However, I sculled at that high rate with the same technique throughout the entire workout. When it became rather easy, I increased the rate and worked on that, over and over again.

"Gradually, my distance grew greater and greater. Finally, I was able to do a full course in this manner. It was not very fast for a short distance, but it was fast enough to win at the normal race distance. . . . I was not worried when my opponent moved away a bit at the start of a mile and a quarter race."886

Joe's son, Roger Burk, remembers the Pocock singles his father rowed. "Dad's first boat was a tear-drop design, with a rather flat bottom. It seemed best suited to planing over the water surface rather than knifing through it.

"Apparently, it was ideally suited to Dad's high-stroking, even-power technique. In fact, one can argue that he developed the technique because of the boat.

"Anyway, George didn't like Dad's technique, preferring the more traditional, and stopped building boats with that design.

"When I was just starting rowing, I remember Dad telling me that he never felt that his subsequent boats were as fast as his first."887

During World War II, Joe commanded PT-320 in the Pacific, sinking at least 26 enemy barges and winning the Navy Cross and the Silver and Bronze Stars for heroism in action.

856 Burk, personal conversation, 2005

857 Dubois, John, Joe Burk Still Pulls a Mean Oar, Main Line Times, Ardmore, PA, April 12, 1956

858 Burk, personal conversation, 2005

859 Palatsky, p. 1

860 Rosenberg, USRA

861 Burk, personal correspondence, 2005

862 Mendenhall, Ch. XIV, pp. 6-7

863 Newspaper clipping collection of Bernard Biglin, John Biglin's great grandson.

864 Mendenhall, Ch. XIV, p. 9

865 Burk, qtd. by Fabricus, p. 38

866 Burk, personal correspondence, 2004

867 Burk, personal correspondence, 2005

868 Burk, qtd. by Fabricus, p. 41

869 Mendenhall, Ch. XIV, pp. 6-7

870 Burk, personal correspondence, 2004

871 See p. xx

872 Time Magazine, July 11, 1938

873 Joe's record was finally broken in 1965 by 1964 U.S. Olympic sculler Don Spero.

874 Burk, personal correspondence, 2004

875 Plaisted, Fred, personal scrapbook, Mystic Seaport Library

876 Rosenberg, personal conversation, 2004

877 www.BritishPathé.com

878 Allison Danzig, The New York Times, August 14, 1932

879 Newspaper clipping, collection of Bernard Biglin, John Biglin's great grandson.

880 Burk, personal conversation, 2005

881 qtd. by Mendenhall, Ch. XIV, p.11

882 Parker, personal conversation, 2004

883 Mendenhall, Ch. XIV, p. 10

884 Burk, personal correspondence, 2004

885 Mendenhall, Ch. XIV, pp. 7-8

886 Burk, personal correspondence, 2004

887 Roger Burk, personal correspondence, 2005

Joe Burk, Sculler

Diamond Scull winner Joe Burk at Henley, 198

Audio: Joe Burk Wins the Diamond Sculls, 1938

Joe Burk was the son of an apple grower in southern New Jersey near Philadelphia. His initial interest in rowing stemmed from a teen-age trip to the IRA."I happened to read about how well California had done in crew. I had never been to Poughkeepsie, scarcely knew where it was, but I found that I could take the train to New York and get on the New York Central to Poughkeepsie.

"I arrived there and didn't have any place to stay because every good place was already filled up, so I asked some bum on the street, and he told me of an old, brokendown hotel where I could eat and sleep.

"It was 1929, and California was the big-shot crew then. I wanted to see the time trials they were having, so I took the ferry boat across the river and went to the California boathouse.

"There was nobody around except the manager, and he showed me the shells and so forth. I found it all very interesting, and when the race came off, he and I dragged a railroad tie up against the side of the building, climbed up and watched the race from the roof.

"Unfortunately, California didn't win that year.

"Late in the day I went back to New York on the train. I stayed up the whole night and got home the next morning tired but knowing that I wanted to go out for rowing."856

Joe had exactly two cents left in his pocket.857

When Joe got to the University of Pennsylvania that fall, he almost missed his rowing destiny.

"I had been captain of my high school football team, and football was the big thing. I hadn't given any thought to the fact that they rowed in the fall in those days, and when I got to Penn, I found out that rowing started the same time that football practice did, so I thought that was the end of rowing for me.

"Then, after football I found out that crew started in on the machines in the winter, and so I met Rusty Callow and gave it a try."858

"He didn't make the first boat that year, but in the words of Callow, 'he combined those qualities of size, strength, skill and spirit' and made the varsity boat his sophomore year."859

According to Allen Rosenberg, "Joe was the epitome of a sportsman at Penn. He won two letters in football and crew, two blankets with a P on them. To have excelled in both in the same year is extraordinary."860 Joe tells me he actually won three letters in crew by the time he graduated in 1934, and Joe's son, Roger, tells me that Rusty actually had George Pocock make an oar with an extra-large blade for him to row with.

Joe: "At the time that I graduated in 1934, Penn planned to enter the Olympic Trials of 1936. To keep in shape in the meantime, I joined the Penn A.C., who had won the European Championship eights in 1930.

"They were coached by Frank Muller, Jack Kelly's sculling coach at the Olympics in the '20s, and he required all of his crew to have had sculling experience, so I was teamed with a young fellow, Tony Gallagher. He was a strong, young kid with no previous rowing experience. We made a good combination in the double and were undefeated.

"It was a good summer, and it prompted me to get a single built by George Pocock. "Gallagher hoped that we might compete together in the double in the Olympic Trials two years hence, but I had other plans, and that was to row in the University of Pennsylvania graduate eight, which was a strong crew."861

So, as Joe trained more and more in his single, he had as a foundation the fundamentals he had learned from Rusty Callow, and he also had as a sculling coach the man who had guided John B. Kelly to three Olympic Gold Medals. In addition, he began a regular correspondence with George Pocock that would last forty years.

But Joe Burk was also a free thinker. He approached his sculling with an open mind. He ended up developing a technique that built on but diverged completely from the 1st Generation Conibear Stroke he had rowed at Penn under Coach Rusty Callow.

Mendenhall: "He proceeded through trial and error rather than any prescribed lesson plan or time-tested technique. The experiment was rooted in Joe's growing conviction that the traditional, orthodox sculling stroke was inefficient and tiring.

"Though it was always seen as a continuous, unbroken cycle, the traditional stroke, even when racing flat out at a rating in the low to middle 30s, experienced some considerable alternation in speed.

"The shell always achieved its maximum speed at the finish of the stroke, and the recovery part of the cycle represented almost twice as much time as the drive through the water. Thus the sculler was traditionally obliged to pick up the boat up again every stroke at the catch.

"By contrast, Joe's eventual goal became clear: to keep the run on the shell virtually constant, with no variation in speed at either end of the stroke and most especially with no check or dousing at either the catch or the finish.

"Burk: 'The slide work is always the same, attempting to keep the slide moving continuously - no stopping, just a change in direction at either end. The arms, legs and back all started together and all finished together.'

"He reasoned that eventually the boat should move faster with less effort once he had shortened the stroke at both ends and conditioned himself to row comfortably at a much higher rating. The faster pull-through was helped by the knees remaining closed at the catch (to produce a quicker, straight-line drive) and the arms starting to break from the very beginning of the stroke."862

His contemporaries termed his technique "unique" and "innovative." In other words, they didn't know what to make of it. Nothing like it had been seen on Boathouse Row for half a century.

But it had been seen before.

Professional oarsman Barney Biglin, commenting around 1920 on a winning high-stroking Belgian crew at Henley, said, "I can't understand why there should be so much surprise in England because the Belgian crew manages to get great speed out of its so-called short, jerky stroke. What else could they get out of it? "863

Barney and his brother, John, were painted by Thomas Eakins rowing their "short, jerky" stroke on the Schuylkill River in the early 1870s. Their forearm development foreshadowed that of Joe Burk.

For years after Joe bought his first Pocock single, he and George exchanged letters regularly, discussing equipment, training and technique.

For years after Joe bought his first Pocock single, he and George exchanged letters regularly, discussing equipment, training and technique."G.C. Bourne's A Textbook of Oarsmanship (1925), already the most thorough, scientific analysis of the conventional wisdom, insisted on at least a 1:3 ratio of pullthrough to recovery as fundamental to all good rowing!

"George Pocock came to recognize the possibility of the short stroke and high rating combined with Joe's training methods.

"'It's a wide opportunity,' he wrote, 'to anyone willing to pay the price.'

"[Joe's reply:] 'It was worth every tortured moment when the shell would feel silky smooth and go like a breeze.'"864

Upon his retirement, Joe wrote: "George Pocock of Seattle not only fashioned and constructed those sleek, slithering sticks of gold that were such a joy to scull, but also helped me no end in the art of sculling them.

"At times I am afraid George must have felt that he was running a correspondence course in the art of sculling, so many questions did I shoot at him by mail. It was he who convinced me that a short stroke would fulfill my requirements. His fame as a builder of racing shells has spread worldwide, but like Paul Revere's prowess as a silversmith, his ability as a sculling coach has been outshone by his other brilliance.

"To me it was a glowing beacon in the darkness of ignorance."865

Recently I asked Joe how he developed his approach to sculling:

Joe: "I tried many versions and came up with a technique that seemed to enable me to go sufficiently fast with a minimum of effort. It was very simple - arms, legs and back all started together and all finished together."866

"Most scullers' rate was about 28 strokes per minute, while mine was 40-42.

"Everyone else allowed one hand to precede the other, so they didn't overlap. I wanted to have them coming into my body at the same time. It required one rigger to be 3 1/2 inches higher than the other! Very unusual! However, it was very comfortable.

"Since I sculled with my hands moving at the same speed and crossing as they approached my knees, if my fingernails were the least bit long, they scraped the knuckles of my lower hand, so I wore a canvas glove from which I had cut off the thumb and fingers."867

"I added some padding made of the fingers that I had cut off, sewing with some heavy, black thread which my brother and I used for repairing baseballs as a kid. "We had a neighbor who pitched for a semi-pro team, and he gave us all the damaged baseballs in payment for being his catcher as he kept his arm 'loose' during the week."868

The Evening Bulletin, Philadelphia, July 2, 1938

Forearms to rival those of the Biglin Brothers

"The slide work [on the pullthrough and the recovery] was always the same, attempting to keep the slide moving continuously - no stopping, just a change in direction at either end."869

"[The technique] was not very fast, but sufficiently fast to win any race that was longer than a quarter-mile or half-mile."870 Sufficiently fast to win any race? Joe Burk is a very modest man.

At the 1936 Olympic Trials, his Penn graduate eight placed second to the University of Washington, and in his single, he placed second to U.S Champion Dan Barrow, who had rowed 7-seat in the Penn A.C. 1930 European Champion "Big Eight."871 That was the last race Joe lost for four years.

Joe won the 1937 U.S. and Canadian Championships, and then won them again every year through 1940.

He won the Diamond Sculls at Henley in 1938 and 1939. He amassed 37 consecutive victories in all, and won the Sullivan Award as the nation's top amateur athlete during 1939.

He won the 1940 Olympic Trials and would have been the overwhelming favorite at the 1940 Olympics in Helsinki, had they not been cancelled because of the outbreak of World War II.

How did Time Magazine describe his 1938 Diamond Sculls victory? "Britons who thronged the banks of the Thames last week for England's No. 1 rowing carnival, the annual Henley Regatta, saw an amazing performance.

"For four days they gaped at a redhaired American sculler, Joseph William Burk, who decisively outrowed his opponents over the mile and 5/16 course, day after day in the elimination heats of the Diamond Sculls, the most famed race in the world for individual scullers.

"'He does everything wrong,' muttered experts and dubs alike. Rowing an extremely high stroke (36 to 45 a minute, compared to an average sculler's 28 to 32), Joe Burk, who weighs 195 lb. and has arms like piano legs, propels his shell with an unorthodox short jerk of his arms and a quick kick of his legs, sits up almost straight at the end of each stroke.

"This freak style he developed two years ago on New Jersey's Rancocas Creek, hard by his father's fruit farm, after rowing in orthodox fashion on the University of Pennsylvania crew.

"He can row for miles at 40, and can maintain a speed of 12 miles an hour over a mile and a quarter course. Last year, after running away with the U.S. and Canadian sculling championships with machine-like ease, oarsmen dubbed him the "rowing robot," and marveled at the power of his arms. "But his brawny arms are nothing compared to his perseverance. In preparing for the Henley Regatta, throughout last winter and summer, the Jersey farm boy rowed 3,000 miles on the narrow, winding Rancocas, with a stopwatch strapped between his toes.

"Last week, 23-year-old Joe Burk was well rewarded. In the final of the Diamond Sculls, dipping his oars 45 times a minute, he streaked through the water as if he had an outboard motor attached to his 26-lb. shell, not only winning the coveted race but doing it in 8 min. 2 sec. - eight seconds faster than the Henley record set in 1905.

"'They'll have to burn all the books on rowing,' sighed onlookers."872

To put Joe's time into perspective, he broke a 33-year-old course record, and it only took another 27 years for it to be eclipsed.873 Diamond Sculls winners didn't begin to consistently row under Joe's time until the late 1980s, half a century after Joe.

How does Joe describe his achievement?

"I must admit that it was done under 'ideal' racing conditions."874

There have been a number of dominating scullers in rowing history, but the only man before or since who approached Joe Burk's innovative brilliance and athletic dominance was Ned Hanlan himself!

Fred Plaisted, the professional sculler who toured Europe with Jim Ten Eyck and actually rowed against Ned Hanlan in 1876, lived long enough to befriend Joe Burk.

He colorfully wrote about his fellow Boathouse Row sculler:

After Joe Burk won the dimond sculls at Henley on the Temes England, an Englishman said to me, 'You people have sent a big farmer to win the dimond sculls. Haven't you got some lords and Dukes like we have to row at Henley? You know, them people that don't work.'

'Yess mister, we have lots of that kind. This country is full of them, but we call them tramps. Everyone works in America.

Even the President of the United States choped wood for a living. Once he choped wood he could not have been a gentleman.'

I swong the right. Two blows struck. I hit him. He hit the floor. He was down to the count of 10."875

Fred Plaisted was 90 years old when Joe Burk won the Diamond Sculls in 1939, and I imagine that the wood-chopping president to which he was referring was Abraham Lincoln, whom he would have remembered well!

American Olympic coach Allen Rosenberg recalls, "Joe did the same thing as Ratzeburg [the innovative crew from West Germany] twenty years later. The rate of striking was so high that he had to cut both ends of the pullthrough."876

In fact, newsreel footage 877 reveals that Burk did not cut the front end of the pullthrough at all.

Joe Burk rowed that 1938 Henley final with a generous +30 degree body angle forward. His position at the catch was reminiscent of Ellis Ward's 1901 Penn Henley crew and Richard Glendon's 1920 Annapolis crew.

Much of his height was in his trunk, and he compressed his upper body tightly enough onto his thighs that his shins tilted past vertical.

His head followed an elegant arc up and away from the catch, and his shoulder lift and body swing were smooth and pleasing to the eye.

Burk's layback was limited to only -5 degrees, despite the fact that Callow had coached him at Penn to lay back -40 degrees or more, but his body swing as a whole was by no means radical. As we shall soon see, his concurrent usage of the legs, back and arms to a relatively upright finish mirrored the evolutionary direction of the 2nd Generation Conibear technique of Al Ulbrickson and Tom Bolles beginning in the early 1930s and reaching its height after World War II.

The Washington crew that beat Joe's Penn eight in the 1936 Olympic Trials had body swing from +25 to -25 degrees, considerably less than the norm of the time.

No. Limiting body swing was not Joe Burk's greatest innovation.

What seemed to set Burk apart was his rhythm, ratio and pacing, his ability to row an entire race evenly at a 1-to-1 ratio and not slow down.

He rowed the entire 1938 Henley final at close to 40 strokes per minute, certainly unique for a single sculler, but there truly is nothing new under the sun, and there had been precedents for Joe's high ratings.

Three years after high schooler Joe Burk had taken a train to watch them in Poughkeepsie, the California crew had won the 1932 Olympic eights by rowing the last 1,800 meters of the 2,000 meter course at 40 or above. They had to do so to match the Italians.

The New York Times: "At no time over the 2,000 meters were the blue-shirted men lower than 39 or 40 strokes to the minute, and toward the end their minimum was 42.

"Italy maintained an extremely high stroke throughout the race, which is characteristic of its style of rowing, featured like the American, by its short back swing, choppy stroke and short slide [my emphasis]."878

The margin of victory over Italy in 1932 was perhaps three feet. And 19th Century professional Barney Biglin used to brag, "Why, man alive, when we were winning championship races so fast that we could not count them, we used to hit it at 50 or even higher during spurts. The 50-to-a-minute stroke consisted chiefly of arm work, and forearm work at that, but it enabled us to get so far ahead that we could take a rest, so to speak."879

Interestingly, the last time Joe Burk ever raced in an eight was at the 1936 Trials, and his Penn graduate boat rowed the entire 2,000 meters at 40. They led for 1,600 meters before being rowed down. Perhaps it was here that Joe got the idea that he could make it those last 400 meters with just a bit more training.

No, Joe Burk's true innovation was imagination!

At the 1939 Henley Regatta, Joe deviated from his race plan, and he nearly regretted it.

"A funny thing happened my second year in the Diamond Sculls during the final against Roger Verey from Poland. He had twice won the European Championships and was really quite a good sculler.

"With the way I rowed, I just learned from long experience never to worry about what happened at the beginning of a race because I knew that I could keep just about the same speed all the way through.

"So in my race with Verey, he went out and took a lead, and I caught up, oh, about halfway down the course.

"There was a strong cross-wind that day, especially there at the halfway point. I knew that my stern post was pointed right at the start float, but I hadn't thought about the fact that the wind was blowing me over.

"All of a sudden, Bang! I hit against an upright on the log boom.

"Luckily, I didn't capsize. My oar was turned up square at the time, and it was knocked out of my hands. I grabbed ahold of it, but by that time, Verey was back ahead of me.

"I thought, 'Boy! I'm really going to have to work now!' and I forgot all about pacing and just rowed as hard as I could.

"I finally caught up to him, maybe a quarter-mile from the finish. I started to go by him, but it was just about all I could do to keep moving.

"I knew he would look over at me, so as I began to go by, I turned my head and smiled at him as though there was nothing to it.

"Immediately, he dropped back, and that's the way I was lucky to win that second Henley victory."880

Just as with the West German Ratzeburg Technique twenty years later, the body mechanics of Burk's rowing technique was mainstream Schubschlag concurrent, but, as Adam would do again in the 1950s, Joe took the rating up, maintaining his smooth power application at a 1-to-1 ratio between pullthrough and recovery.

Just as with the West German Ratzeburg Technique twenty years later, the body mechanics of Burk's rowing technique was mainstream Schubschlag concurrent, but, as Adam would do again in the 1950s, Joe took the rating up, maintaining his smooth power application at a 1-to-1 ratio between pullthrough and recovery.Interestingly, at Henley in 1938, British journalists saw a similarity between Burk and Steve Fairbairn: "He has invented a sort of Jesus Style of sculling [i.e. body swing insufficient to qualify as Orthodox]. He limits his swing strictly backwards and forwards, and within the narrow and highly efficient arc, he sculls with superb precision at 40 all over the course.

"His boat runs well with scarcely any hesitation or bounce . . . apart from the general crispness of his blade work, the strength of his wrist work at the finish is worth watching. . . .

"If he wins, he will have many imitators.

"It has been said that there never has been a man capable of sculling in Burk's style, but then no sculler of pretensions has ever been allowed by his advisers to try.

"Though it must need good wrists and a sound mind, there is some reason to suppose that this, in fact, is the least exhausting and most efficient way of propelling a sculling boat. No energy is wasted on pinching a boat, and the body is never in an exhausting position which hampers breathing . . . He is, in fact, the best balanced sculler ever seen.

"His short stroke, aided by unremitting practice, have made him so, and though his form may not be elegant [i.e. insufficient body swing] and he buries his oars a little too deep when tired, it seems as if from his time he would have relentlessly rowed down all the giants of the past . . . with his unemotional 40 strokes a minute."881

There was good reason that British journalists and Time Magazine were impressed with Burk's wrists. As Burk protege Harry Parker recalls, "He had massive forearms. When I was sculling with him, I remember that was the first feature that you would notice.

"One of the hallmarks of Joe's sculling was breaking the arms early and bending them continuously through the stroke, which, as he admits, put a tremendous strain on him, and it took quite a while for him to develop that strength.

"I talked to a guy at Penn who was in the gym with Joe and used to describe some of the workouts he did with these ball weights, you know pulling them, and he did phenomenal workouts strengthening up his arms, his forearms in particular."882

Of course, gym workouts were not Joe's only land training. At his farm, "climbing up and down the ladders with thousands of 50-pound baskets of apples provided him with plenty of weightlifting."883

I asked Joe what it was like to row the Burk Technique.

Joe: "When I first attempted it, I could go only a short distance before fatigue set in. So, I decided to scull every stroke in this manner.

"I used to practice day after day on the Rancocas Creek, where we had a farm. I even had to dodge the floating ice during the winter. I would be all alone - miles away from my little dock at home. If I had struck an ice-flow, it would have been curtains. I was just plain lucky."884

According to historian Mendenhall, "The outings began with short stretches to warm up with and then longer pieces at racing stroke, 36 the first year, then up to 38.

Eventually he was sculling for 20 minutes at 40-42. Everything was directed to eliminate all wasted motions, anything that might reduce the rate of striking with the slide continuously moving. The speed on the recovery was the same as on the pullthrough."885

In Burk's words, "I gradually adjusted to it. However, I sculled at that high rate with the same technique throughout the entire workout. When it became rather easy, I increased the rate and worked on that, over and over again.

"Gradually, my distance grew greater and greater. Finally, I was able to do a full course in this manner. It was not very fast for a short distance, but it was fast enough to win at the normal race distance. . . . I was not worried when my opponent moved away a bit at the start of a mile and a quarter race."886

Joe's son, Roger Burk, remembers the Pocock singles his father rowed. "Dad's first boat was a tear-drop design, with a rather flat bottom. It seemed best suited to planing over the water surface rather than knifing through it.

"Apparently, it was ideally suited to Dad's high-stroking, even-power technique. In fact, one can argue that he developed the technique because of the boat.

"Anyway, George didn't like Dad's technique, preferring the more traditional, and stopped building boats with that design.

"When I was just starting rowing, I remember Dad telling me that he never felt that his subsequent boats were as fast as his first."887

Joe Burk and History

Joe had very little lasting influence on the history of sculling technique for two reasons. First, while he was active, his success was largely attributed to his phenomenal athletic ability instead of to his technique, which no one else believed they could match and which flew in the face of conventional wisdom. Second, World War II intervened, and when the sport resumed after the war, Joe had become a dimly-remembered legend instead of a role model. It was only as a coach that he would leave his mark on the next generation.

During World War II, Joe commanded PT-320 in the Pacific, sinking at least 26 enemy barges and winning the Navy Cross and the Silver and Bronze Stars for heroism in action.

856 Burk, personal conversation, 2005

857 Dubois, John, Joe Burk Still Pulls a Mean Oar, Main Line Times, Ardmore, PA, April 12, 1956

858 Burk, personal conversation, 2005

859 Palatsky, p. 1

860 Rosenberg, USRA

861 Burk, personal correspondence, 2005

862 Mendenhall, Ch. XIV, pp. 6-7

863 Newspaper clipping collection of Bernard Biglin, John Biglin's great grandson.

864 Mendenhall, Ch. XIV, p. 9

865 Burk, qtd. by Fabricus, p. 38

866 Burk, personal correspondence, 2004

867 Burk, personal correspondence, 2005

868 Burk, qtd. by Fabricus, p. 41

869 Mendenhall, Ch. XIV, pp. 6-7

870 Burk, personal correspondence, 2004

871 See p. xx

872 Time Magazine, July 11, 1938

873 Joe's record was finally broken in 1965 by 1964 U.S. Olympic sculler Don Spero.

874 Burk, personal correspondence, 2004

875 Plaisted, Fred, personal scrapbook, Mystic Seaport Library

876 Rosenberg, personal conversation, 2004

877 www.BritishPathé.com

878 Allison Danzig, The New York Times, August 14, 1932

879 Newspaper clipping, collection of Bernard Biglin, John Biglin's great grandson.

880 Burk, personal conversation, 2005

881 qtd. by Mendenhall, Ch. XIV, p.11

882 Parker, personal conversation, 2004

883 Mendenhall, Ch. XIV, p. 10

884 Burk, personal correspondence, 2004

885 Mendenhall, Ch. XIV, pp. 7-8

886 Burk, personal correspondence, 2004

887 Roger Burk, personal correspondence, 2005

SUPPORT ROW2K

If you enjoy and rely on row2k, we need your help to be able to keep doing all this. Though row2k sometimes looks like a big, outside-funded operation, it mainly runs on enthusiasm and grit. Help us keep it coming, thank you! Learn more.

If you enjoy and rely on row2k, we need your help to be able to keep doing all this. Though row2k sometimes looks like a big, outside-funded operation, it mainly runs on enthusiasm and grit. Help us keep it coming, thank you! Learn more.

Related Stories

Rowing Features

This Week's Best of Rowing on Instagram 4/27/2024

April 27, 2024

In the Driver's Seat, with Olivia Seline

April 23, 2024

Rowing Headlines

2024 Inaugural CRCA Athletes to Watch

March 13, 2024

World Rowing suspends Serbian Rowing Federation over financial debts

January 23, 2024

National Rowing Hall of Fame ® Class of 2023 Announced

October 5, 2023

Advertiser Index

- Bont Rowing

- Calm Waters Rowing

- Concept 2

- Craftsbury Sculling

- The Crew Classic

- CrewLAB

- Croker

- Dad Vail Regatta

- Durham Boat Co.

- Empacher

- Faster Masters

- Filippi

- Fluidesign

- h2row.net

- HUDSON

- Live2Row Studios

- Nielsen-Kellerman

- Oak Ridge RA

- Peinert Boat Works

- Pocock Racing Shells

- Race1 USA

- Rockland Rowing Masters Regatta

- RowKraft

- Rubini Jewelers

- Vespoli USA

- WinTech Racing

Get Social with row2k!

Get our Newsletter!

Enter your email address to receive our weekly newsletter.

Support row2k!

Advertiser Index

- Bont Rowing

- Calm Waters Rowing

- Concept 2

- Craftsbury Sculling

- The Crew Classic

- CrewLAB

- Croker

- Dad Vail Regatta

- Durham Boat Co.

- Empacher

- Faster Masters

- Filippi

- Fluidesign

- h2row.net

- HUDSON

- Live2Row Studios

- Nielsen-Kellerman

- Oak Ridge RA

- Peinert Boat Works

- Pocock Racing Shells

- Race1 USA

- Rockland Rowing Masters Regatta

- RowKraft

- Rubini Jewelers

- Vespoli USA

- WinTech Racing