Back in early 2020, the art museum at Princeton University had set up for an exhibition of the best and most influential photos from Life Magazine. I poked around the preview, and noticed that the lead photo was by Co Rentmeester, with whom I had exchanged emails over time regarding mundane rowing stuff - regattas, classifieds, etc. - as well as his film The Perfect Stroke, perhaps the first full-length film about rowing.

Before I got to see the show, the pandemic hit, the museum shut its doors, and the exhibition was online only. Co was mentioned in interviews and presentations about the exhibit, and while there are tons of rowers who do amazing things outside of rowing, Co's return to rowing after an exemplary career as a photographer, as well as the fact that here at row2k we spend a ton of time looking through lenses, inspired a call to Co to talk about his rowing, coaching, and his photography both in and out of the sport.

During his career as a photographer, Jacobus 'Co' Rentmeester published countless photos with Life, National Geographic, Sports Illustrated (including six covers), the New York Times, and others; was named Magazine Photographer of the Year and earned at least two World Press Photo of the Year awards (this one from Vietnam and the Mark Spitz photo embedded below); published famous and iconic photos of the Vietnam War, the Watts riots, wildlife, the Olympics (for good and bad - Co took the photos seen around the world of the Munich hostage crisis as well as heaps of athletes in action, including a very famous photo of Mark Spitz), sports that include a photo of Michael Jordan that was copied by Nike resulting in a Supreme Court case, the 1969 Mets, and more. Life chose Rentmeester's photograph on premature babies for its last monthly magazine cover in May 2000.

Due to copyright issues, we are not confident we can post Co's photos on row2k on a long-term basis, so have opted for approved IG embeds here - and you can see many of his most well-known and sometimes world-changing photos at What Meets the Eye: The Photography of Co Rentmeester.

row2k: You had a dual, triple, quadruple career in sports and photography, so I thought it would be interesting to talk about it - certainly for me, and hopefully for our readers.

Co Rentmeester: Well, I hope I can make it productive for you. Let me put it that way.

row2k: Fair enough; how did you get started in rowing?

Rentmeester: I was raised in a typical Dutch community, and my father thought that one of the civilian things I had to do in life was to learn ballroom dancing when I was 11 years old. Normally, he was never interested in any kind of a sort of civil duty or civil thing, but he thought that I had to know how to learn how to dance the tango or the waltz or the cha-cha and so on. On Wednesday afternoons, I would go to a dancing class in Amsterdam, where I met a young lady who happened to row at a civilian club called Willem III in Amsterdam.

While we danced and talked, she invited me to come down to the rowing club for the first time and see what it was like, and that was how I started.

When this young lady asked me to go to this club, I was received well, but her fellow friends (male friends who looked at me rather skeptically) thought I was not cut out for anything, which became immediately a stimulation for me, and that actually is the reason why I just really stepped into rowing in a sense.

I wanted to compete. It immediately came to me. 'It would be nice to row against these guys and beat them on the water.' That is exactly what happened. We all became friends later on, but that was the initiative.

row2k: So classic! You were still young then.

Rentmeester: Yeah, I was 14 when I rowed my first junior race of 750 meters on a small river called the Zaan near Amsterdam; I thought I would die in that little piece.

row2k: At what point did you become 'good' at rowing?

Rentmeester: I just kept slowly going, getting better, and I became a junior champion in the singles when I was 17.

But I had to go into the Dutch draft, which was necessary because we were in the Cold War period at that time. I first wanted to go into the Air Force, but my dad had to give permission, and he stopped that because, actually, he was petrified of flying himself.

That interrupted my rowing for 18 months. When I started up again, and it took me about a year to get going again, because I had my tonsilitis done and I had an appendix taken out.

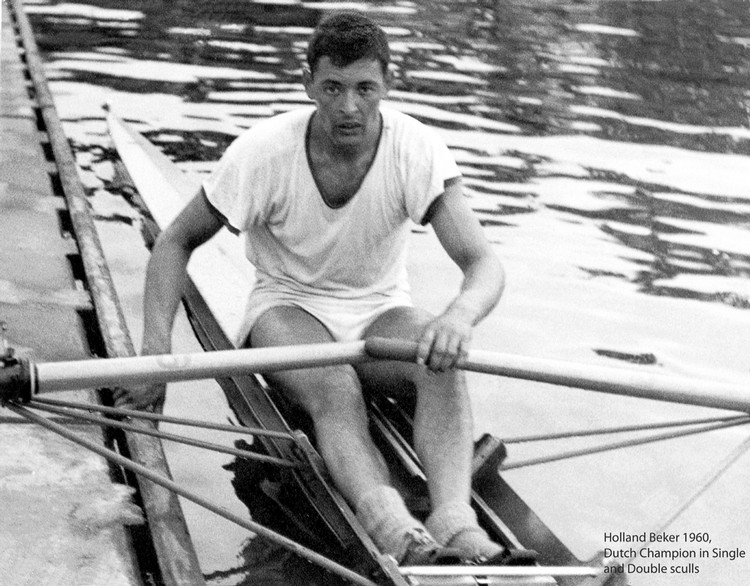

But on the question 'when did I really go faster?' it was late 1958. Then, I became an elite champion in the singles in '59. Then I rowed in a double in Lucerne, and nobody had ever heard of us, but we won Lucerne in the elite doubles at that time. That was immediately a jump to a higher level.

In '59 and '60, I had won some very major important races in the Netherlands, and then we went to the Olympics.

(Watch video of Rentmeester winning the Holland-Beker here.)

row2k: You were in the single, and then the double, is that right?

Rentmeester: Exactly. But essentially, my career as an elite rower was really only two years. And then, as it goes in Europe, my father said, 'You have to go on your own,' so I had to go and find a career which then I did.

By that time, I had some connections with some people in the United States. It becomes a very long story now, but briefly, I was invited to go to the US, and I went to school at the ArtCenter College of Design because I had an underlying hobby even while rowing, and that was always little cameras and Kodak little booklets and film and shutter speeds. That always fascinated me.

While I was rowing, I would sit in a train going from the city of Arnhem which is about 65 miles away from the rowing course daily to practice. When I was sitting on the train, I read these little booklets of Kodak that were translated from English into Dutch about density of film and color and graphs and black-and-white and composition and these sorts of things. It fascinated me as a hobby, so I was doing it as a hobby with rowing.

In Rome, I met the owner of American lumber company in Anderson, California, and he asked me to come over, and he would sponsor me. He would lead me then to become an executive in the company -- selling and buying lumber and all that.

At that time, I had no better idea of what I was going to do (meaning civil life) but then, to follow-up his invitation, I went to California, and I went to college (Shasta College in Redding) to spruce up my English and, at the same time, see how the business was.

It became a rather deep disappointment within about six or seven months.

row2k: How so?

Rentmeester: I felt that it was just sort of a black hole that I had ended up in. But one of the things that was outstanding is there's always something in life that lights a candle. There was a gentleman there who was the principal of a high school in Anderson, California. His name was Robert Peckler, a fine guy. He and I were playing tennis a little bit while I was still running like crazy, every day on the track because I was still in this mode of keeping in a super strong kind of physical condition. I was lifting weights while still going to classes out there.

When he saw that I was not happy anymore with the job, he said, 'Well, why don't you go and take a look at the ArtCenter College of Design in Los Angeles?' He said, I've seen your pictures. I think you should see what they think. Send them your photographs and see if they want to take you in.' I followed that up. A big switch in life.

I ended up at the ArtCenter College of Design which is a major art school in the United States, and got a scholarship after two semesters, while still working at a gas station for the next three at night to make some money. I worked my way through and got a BA in professional arts in '64 or '65 and I was already working for Time Magazine - small little pictures.

At one point, I came in and they asked me to do something for Life Magazine, because I was just a young photographer. They needed somebody to shoot a quick photograph. That was just the tiny little opening that started my career with Life Magazine.

row2k: Do you remember what that assignment was?

Rentmeester: Yes, the first assignment was rubella, or German measles. It turned into a cover and ten pages of Life, but it started as a simple request to go out to do a few black-and-white pictures.

row2k: Of young people with measles, something like that?

Rentmeester: There was a young woman, and the fetus evidently can be affected by this particular virus, and there was a big debate at that time of what to do with this and so on, and Life ran a medical story on that.

I had this lady that let me into her life - a young mother. She was pregnant and she already had an earlier child. I took some pictures and became sort of emotionally involved with that and did the best I could. It just turned out to be the first start of what I call a little photographic essay on the problem.

Three months later, I walked into the Life office in Beverly Hills in California, and they said, 'Would you mind going into Watts?' I said, 'What's going on in Watts?' 'Well, they have some disturbances. There are some fires going on, looting, but you don't have to go if you don't want to.' I said, 'No, I'll go.'

I got myself a little rental car, I put on a Bethlehem steel hardhat that I had from another assignment, and went into the situation on Imperial Avenue in Downtown Los Angeles, and it all started right in front of me. Now, that particular essay was another cover at Life, and 13 pages. Suddenly, you know, I was on my way.

row2k: How did you start the hobby of photography when you were young? How did you get your first camera?

Rentmeester: My father was an avid fly fisherman, and he wanted to go to Norway (which is still a pretty good ways from Amsterdam) to an area called Laerdal where there was a tremendous fly fishing on salmon and sea trout and just name it. He wanted to always take me with him because that was his hobby, and I would retrieve lines and fishing rods for him when I was nine or ten.

He had a priceless kind of a camera during that time. Right before World War II, my mother (who had died when I was young) had given him a Rolleiflex.

Now, a Rolleiflex at that time was like the Ferrari of cameras, and this Rolleiflex was, for me, a magic box that sat there in the living room in the bookcase in a green leather case. I would open it and I would take the camera out and I would admire the two little lenses that were staring at me. You know, this was like magic to me. This is really how photography got into my soul.

row2k: Do you think there is an affinity between rowing and photography? Or was it just two things that you happened to do?

Rentmeester: No, I think both were exclusive in a sense, but the rowing was always extremely much more important to me because it was part of my young male ego to want to compete, and that overwhelmed all other reasons. The photography was a beautiful thing, but it was relatively passive. I needed action. I needed power, and that was in the rowing.

row2k: Later on, you had some very intense photo assignments. You were a war photographer for a long time. Do you think that your interest in these intense situations with rowing helped you or affected your photography in the field?

Rentmeester: Not really.

After the Watts situation - I mean, I was not a fool when I went in there. I think I might even describe myself later on as I was a little bit of a fool, but I felt that I was young and strong and I could take on anything, and I could in a sense - but not if you have a group of very angry people around you, and that happened a couple of times.

When it came out, I had this cover on Life Magazine - exclusively as a white European photographer and coming out without any kind of a scratch. I knew at the time that, for instance, the editor of Newsweek Bureau in Los Angeles was hit over the head with a two-by-four and ended up for months in the hospital without becoming conscious again. It could have gone another way completely, but I was aware of what kind of dangers you walk into, and you have no choice as a photographer.

If you want to get something on film, you need to be there. You cannot lean back and judge from a half a mile away, talking to a cop about what's happening out there. And the same thing applies in the world of war, unfortunately. You need to go be there in the front, and I did that for two and a half years.

I was wounded in Vietnam, I was shot through the hand, then I ended up after that in rehabilitation because I picked up malaria. During the secret war that they said Nixon had at the time in Laos that was associated with the Vietnam War, we wanted to do a story at Life Magazine to show that war. I was sent out as a photographer to cover that and ended up in the highlands, in little holes and mosquitos. That is where I picked up malaria and that sent me back to the mainland again to get that out of my system.

row2k: In these situations, are there any that are most striking or most stay with you from your time as a war photographer that you'd be able to relate? Were there any situations during your time as a war photographer - or even not as a war photographer - similar to Watts that you could share that you think were extremely intense, memorable, or even very happy endings?

Rentmeester: Oh, yes, indeed; I could write a book!

Sometimes in the world of photography, but in my world of photography that was journalism, especially Life Magazine - it was the main outlet in those decades, as you recall - the idea was that, when you go out you don't just have a nice photo, but you have a beautiful essay - telling a story in pictures.

Sometimes it can be a very benign situation, and sometimes a passive situation turns suddenly into very extreme violence, or death almost. For instance, when I did a polar bear story, I was with a Canadian wildlife specialist from the government doing photography on polar bears. Here we are, and we were charged by two of them.

Things like that are very dangerous, and you don't want to do any harm, but to get it on film, you cannot anticipate these things.

It's the same thing if you go and take pictures of turtles in the small green turtle island off the east coast of Borneo, in the province of Sabah, where you have this incredibly beautiful natural event that happens once a year where, from thousands of miles away, the female turtle somehow knows exactly where to go on that spot on the earth where she was born and go back and dig the hole in the sand on the little beach. That island is no bigger than about two square miles.

On that little beach right there, thousands of turtles show up during the night, and they dig these holes, and they drop about 110 little ping-pong ball-sized eggs, bury them, and then they slowly work their way back into the ocean; very exhausting, the whole thing. That kind of a beautiful thing, I have done - animal stories, including the one that became one of the most popular covers of Life Magazine, the snow monkey of Japan.

row2k: What is the story of that photo?

Rentmeester: At Life, we had what I call a wildlife editor, Pat, who would assign me to various wildlife stories. That happened after Vietnam, because, obviously, I didn't want to go back to any war situations anymore.

So after I was healed up a little bit, they sent me for my first assignment to do a story on the orangutan. The orangutan is an endangered species ?- a wonderful ape. You mostly find them in South Sumatra and then in Kalimantan which is a part of Borneo, that particular area.

Borneo itself, on the east coast, has a province called Saba, and they have a special collection point because one of the things that you may know is that orangutans were and still are popular pets for seamen on maritime ships.

row2k: I did not know that.

Rentmeester: It is unfortunate; what they did was kill the female and capture the young, and sell them as pets to seamen traveling the world. The wildlife service wanted to stop that ,so they collected these juveniles to bring them back to the jungle. I spent two or three days with, and Life ran a cover on that also. But the one that really hit the spot as far as monkeys are concerned is the snow monkey. That won many awards, and everybody seems to remember this cover.

row2k: You ended up then photographing a lot of sports. You have the Mark Spitz photo, as well as a photo of Michael Jordan flying through the air.

Rentmeester: I expected that would come up in this conversation - the Jordan situation.

row2k: Yes.

Rentmeester: Well, that's a book by itself - but the picture of Jordan - what I call the "Jumpman" logo - was ripped off by Nike. I sued, and I took it all the way to the Supreme Court.

row2k: Wow.

Rentmeester: They didn't want to deal with it because, basically, the big corporation has so much strength that Nike managed to duck it all the way to there (the Supreme Court). And photography was considered by some of the judges as an inferior art - but the bottom line is, yes, they did rip it off, and I tried to take it as far as I could. It is a painful period, and I lost at the end anyway, and it's a done deal. You know what I mean?

row2k: I do.

Rentmeester: The picture that I took is considered to be one of the most evocative photographs ever taken in the last hundred years, and Time did a special book on photographs that are considered to be historically the most important ones, and this one made it into that category.

There were three or four people from National Geographic - Tom Kennedy and a few other people, who stepped up and got it as far and the Ninth Circuit. It went on for four years. I have to say that, as an artist in photography, I had very good legal representation. I cannot really complain about that, and I did get it all the way to the Supreme Court, who chose not to hear the case. They didn't make even a decision.

row2k: I wanted to ask what brought you back to rowing, and talk about your movie as well as your coaching - unless you have any other thoughts on your photography .

Rentmeester: One thing I do have to say, Ed, is just the absolute admiration (and, actually, some envy) on the modern technology situation with regard to what can be shown in rowing - the intensity of it, the beauty of it. It is just amazing what the drones can show you above the crews rowing. It is amazing when you see the high-speed lenses that now are fully automatic and focus on the details. It is gorgeous.

For me, as a photographer, rowing has never been shown as well as in the last four years.

row2k: When you were called on to do rowing assignments when you were a professional photographer, did you shy away from those, or did you want to do those?

Rentmeester: I can answer that question in another way. When I decided to leave rowing, when I went to the ArtsCenter, when I left for the United States, I closed the door on rowing at that point - because I could have stayed easily four more years and go to Tokyo for the Netherlands in a double scull or in singles, or even longer.

I was making a career choice; I had no silver spoon in my family. So when I got to the ArtsCenter for college, the main thing was to succeed and to really make my step as I could, what helped me enormously then was that, for months and days, I worked nonstop with the same intensity as I would approach my training with rowing.

It was complete focus, and that helped me to excel or just do better in photography than other people do.

Toward the end of the time when I was doing my photojournalism, from 1962 through 1996, I ended up in the hospital. And I decided something had to change, because I was eating too much, and I was heavy. There was absolutely no thought or effort to anything that was not related to photography, and it had taken an enormous toll on my body, and it was very obvious.

From that moment on, I started to decrease my photography business, and started to play more of a role in the world of rowing again. I got myself a single from Hudson, and here in front of my house, we have water to row in, so there was no excuse not to. So I started to work my way back into the world of veteran rowing.

row2k: Talk about your movie a bit.

Rentmeester: Of course, there was always this drive. If I go back in the world of rowing, I need to compete against the guys of my age. So I went to Glasgow, and I won the double out there in the World Masters with a friend of mine, Jan-Maurits de Jonge. He passed away; I rowed the double with him, and we were great friends. For four years, I went to Europe to race World Masters, and in 2004, on the way to Hamburg, I said, 'You know, it would be really nice if we can do a documentary of rowing, and focus on the single sculler's mind.'

The seed idea was the life of a single sculler. That was the start whereby we would talk about the hardships and the loneliness, and the fights against yourself and fatigue, and so on. This is the specific thing that you have to learn and to appreciate (to row the single).

That was the very basic idea, visually to incorporate all that in some kind of a script. That was on that trip with Jan-Maurits to Hamburg, where I won the single in the Masters Worlds, and he did the same in a mixed double.

There was the whole camaraderie of the project, and the movie started to take a life of its own. We got some people interested in getting some money, and I had some ideas of how to immediately get some evocative, kind of a poetic sense of what sculling is like with beautiful light, and that's how that started.

row2k: As a rower and a filmmaker and photographer, when you saw the finished product, did you feel that you had captured what you were trying to capture? Or was there still something about rowing that was hard to capture?

Rentmeester: In hindsight, I was very happy with the images that I had as a cinemaphotographer. As a budding director, the film has a lot of faults. It doesn't really have a coherent story. There's a collection of quotes from very famous rowers in the Netherlands, and then some pieces together. But to say it is a documentary of the soul of a single sculler, I am not sure that is appropriate; I didn't do a very good job.

row2k: (laughs) Some people disagree. The reason I ask is that people try to explain our sport all the time, and they have trouble doing this, so I wondered if you also found that hard to do.

Rentmeester: Yeah; I just want to self-critique what I did; Jan-Maurits was the executive producer, and he helped with all of that, and I put it creatively together, so I'm responsible for the storyline. But, no, I could have done a better job. In fact, if I had cut the movie - it's too long, I think. If I had kept it to about 20 minutes, and take the confusion out of the old sequences from the Netherlands where, of course, I fell in love with them and I overwrote where you see the old situations of people rowing in a pair, and the boats, and the atmosphere and the high hats and the Queen of Holland there. I had to put that in.

Of course, the reason is that there is a part of the movie about the Holland-Beker Trophy. That is an extremely internationally known world event. Mahe Drysdale won it four times.

row2k: I rowed in it.

Rentmeester: Oh! So, you know all about that. So I had to get that in the movie also. But by adding all these various elements, I diluted really my own stuff in a sense. The focus was all over the place. The initial focus was really the heart and the soul of the single sculler. That was the story I wanted to tell.

row2k: That makes sense. I'm interested in this thing where we love this sport and we're always telling everybody how special it is and how it can change your life, but we can never articulate what the heck that is. Here, you had actually tried to do it in a formal way.

Rentmeester: At that time, I did some photography and cinemaphotography of rowing that had not shown the sport with that particular kind of intensity and beauty. So that I feel I did, and I sort of opened up a lot of eyes to the community and the world that deals with rowing, and the photography of it as well.

After that, of course, a lot of people just started to do similar things, and the Germans practically copied my movie (including almost the whole script) in a German way.

row2k: Oh, my gosh. Tell me about your return to coaching, and your current coaching.

Rentmeester: The Veterans rowing was still very, very important to me. Now every year, I was engaged - going to Europe or I was going to Boston to row the Charles in singles, and I won the big hammer at the C.R.A.S.H.-B, when I was 75.

But then I noticed that I was really getting extremely worn out after a certain event of that kind of intensity, and I became concerned. By that time, I also knew that I had some events of A-fib heart situations. From that moment on, it just really was a rapid decline whereby my heart just couldn't keep up with the will of competing.

row2k: And you started coaching.

Rentmeester: I just loved that because, here in the area, we have the water, but we don't have the enthusiasm. The local population is still very much, in Long Island, New York, the eastern side of Long Island is mostly focused on baseball and football, some soccer, but rowing? Miniscule. It's very difficult to find parents and kids enthusiastically stepping up into it. We had a rowing club for about ten years that I initially started as the owner of it; East End Rowing Institute is really the official name.

I started that around 2002. We tried to expand slowly. At some point, we had maybe about 80 members, but everybody just wanted to row a little bit and drop the equipment and walk away. There was no particular love for one, keeping the equipment in shape, two, to share some social events whereby camaraderie would just create some club spirit and hold things together to get youngsters to enter and to compete with each other in high school situations.

I was the only one, so at some point I drifted away without any official ado, I accepted some serious young kids that wanted really to compete and get better. They have gone on to Columbia, Penn, Princeton, Cornell, four or five different universities; we had some kids that really did well.

row2k: That's great.

Rentmeester: These kids were just willing to stay with me. We took a double to Amsterdam, and it was a trip of a life for the kids. There was a lot of joy in it, it wasn't really a money thing. This was just trying to teach kids discipline and share in the beauty of sculling, to row your heart out and compete, and they did. It was just as glorious for me as it was for them.

I have a new Filippi single here, and sadly because of the heart problems I have rowed it only three or four times, but Danny O'Neill, who went to Cornell and did very well, winning the IRA in the lightweight eight, got in the single here on the creek, and gloriously he was just zipping over the bay. It was very satisfying to see my boat running out there. There's always a way of getting joy out of it when you see the beautiful shell run through the water up there.

row2k: How has the sport of rowing changed in the years since you were rowing and photographing and making films?

Rentmeester: My sense is, and I don't know if you agree with it, but the general interest of the public has changed. I remember the first time, I went to the Head Of The Charles, there were thousands of people along there and on the bridges. Thousands. You couldn't move a car.

I thought it was tremendous that the sport would draw that kind of a thing. In the Netherlands 30 or 40 years ago, the River Amstel would have on both sides just hundreds of thousands of people packed. Ten rows from the waterline, all the way up, cheering and waving their black hats and stuff like that. Horses going around; you name it. That kind of public enthusiasm is not there anymore.

It's the same thing at the Holland-Beker. There used to be thousands of people on the stands and sitting on green lawns and all that. Now, it is really a smaller, elite group of people and parents that want to see their kids rowing and/or are ex-rowers from universities and so on.

We've lost a lot of what I call the general public's interest.

Obviously, what has really just come into more public interest is women's soccer, but rowing, I tried everything. I tried to get the film crews out from the local news and Channel 12 here to see if I can and they can show a little bit the young kids training here on the beautiful water. Unfortunately, I had very little success.

row2k: We touched on times you were called on to do a rowing photo assignment. Were those easier for you or harder for you?

Rentmeester: Oh, no, I do love that, obviously. It was for an article written by Ralph Graves, the managing editor of Life at that time. It was obviously flattering to me, and I may be a little self-serving, that he sent me out. He exaggerated to say that this was really the story of a lifetime, but I just loved to do a story because that obviously fell into an area that I had not done, and that I was given the privilege of doing a story for Life Magazine of my own choice - and I picked rowing. That was not very difficult, and they let me. It was an eight-page essay, and it was pretty good, in the sense of the execution; I liked it.

It centered around Jim Dietz, who is a terrific guy; , so if you're talking about an American oarsman and a spirit of a guy, I mean, Jim Dietz is certainly it.

row2k: The picture that you sent me of him in that rough water was unbelievable. Oh, my gosh.

Rentmeester: Remember this was still the seeds of the plight of the single sculler. The agony of it - if you've rowed, it doesn't matter, but you go out there in the weather. That was still the seed even of the movie too--the single sculler has its own mind, its own tides with egos and defeat and competition and so on. That was part of the reason that I took him out (in those conditions). I said, 'We've got to go! It's just the right weather for me!' He thought I was crazy.

row2k: Was that at the New York Athletic Club?

Rentmeester: Yeah. How did you figure that out?

row2k: I've rowed out there in those conditions.

Rentmeester: Exactly!

So it is painful to have this new single sitting down there without being used, but I try to make it up a little bit with keeping young kids on the water, and that is some kind of a compensation.

row2k: It has been great to talk to you, thank you very much, I really appreciate it.

Rentmeester: I appreciate the interest.

If you enjoy and rely on row2k, we need your help to be able to keep doing all this. Though row2k sometimes looks like a big, outside-funded operation, it mainly runs on enthusiasm and grit. Help us keep it coming, thank you! Learn more.

Comments | Log in to comment |

There are no Comments yet

| |

- Bont Rowing

- Calm Waters Rowing

- Concept 2

- Craftsbury Sculling

- The Crew Classic

- CrewLAB

- Croker

- Durham Boat Co.

- Empacher

- Faster Masters

- Filippi

- Fluidesign

- h2row.net

- HUDSON

- Live2Row Studios

- Nielsen-Kellerman

- Oak Ridge RA

- Peinert Boat Works

- Pocock Racing Shells

- Race1 USA

- RowKraft

- Rubini Jewelers

- Vespoli USA

- WinTech Racing

- Bont Rowing

- Calm Waters Rowing

- Concept 2

- Craftsbury Sculling

- The Crew Classic

- CrewLAB

- Croker

- Durham Boat Co.

- Empacher

- Faster Masters

- Filippi

- Fluidesign

- h2row.net

- HUDSON

- Live2Row Studios

- Nielsen-Kellerman

- Oak Ridge RA

- Peinert Boat Works

- Pocock Racing Shells

- Race1 USA

- RowKraft

- Rubini Jewelers

- Vespoli USA

- WinTech Racing